February 2, 2023

A Lifelong Love

Ever since I was a little girl, monarchs have fascinated me. I grew up surrounded by a field of wildflowers that was surround by woods with a river running through it. Most of my time was spent in this landscape where my curiosity was nurtured and my love for the natural world bloomed. Fast forward to adult life where my love of monarchs has bloomed even brighter and I’m doing something about it.

Wings Lost

In 2003 I married someone I shouldn’t have trusted. For ten years I was not allowed in the public without him, I was kept inside at whatever location we lived at from Rhode Island to Maine, and anything I loved was criticized by him, especially my love of butterflies. In the darkest times of that decade of abuse, I forgot who I was, I traded my identity in favor of survival and became an empty shell of who he wanted me to be— his puppet. Ten years later, now with two daughters, I knew that I needed to keep them safe, so I left with the help of my caring family and friends who had been shielded from the dark reality we were experiencing.

Finding My Wings

As a survivor of domestic abuse and captivity, when I rediscovered monarchs and their astounding transformation, my own transformation began to take place. I had forgotten that side of me— the side that could hope.

New Beginnings

It began as just a few caterpillars, sharing their metamorphosis with my daughters as my own mother had with me. I went to grad school in each summer from 2014-2019, but with that complete, and able to stay in Maine for the duration of the summer, as I was observing my local monarchs, I realized they were being destroyed with the hay harvest in the field I loved so much. (As an adult, I still live near my childhood field.) My mother tells me I stood in front of the tractor and had him wait so I could clip some milkweed in front of him, in case it had caterpillars or eggs on it. Because of my PTSD sometimes I don’t have as sharp of a memory as those around me, and they help me piece events together at times.

Threats

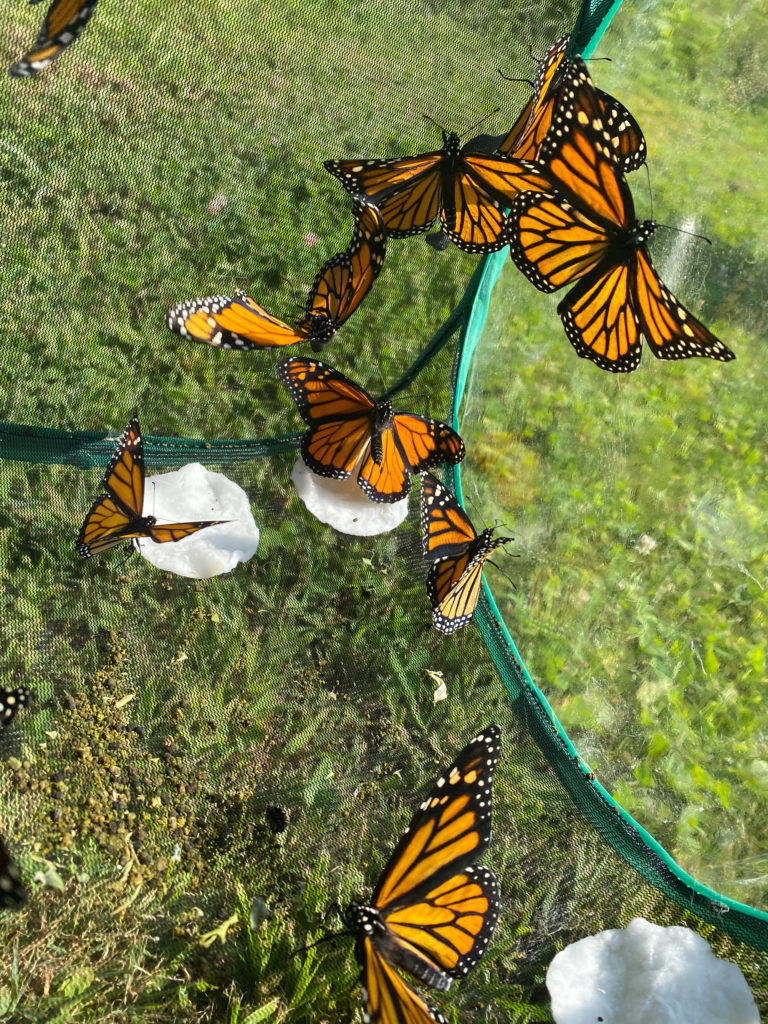

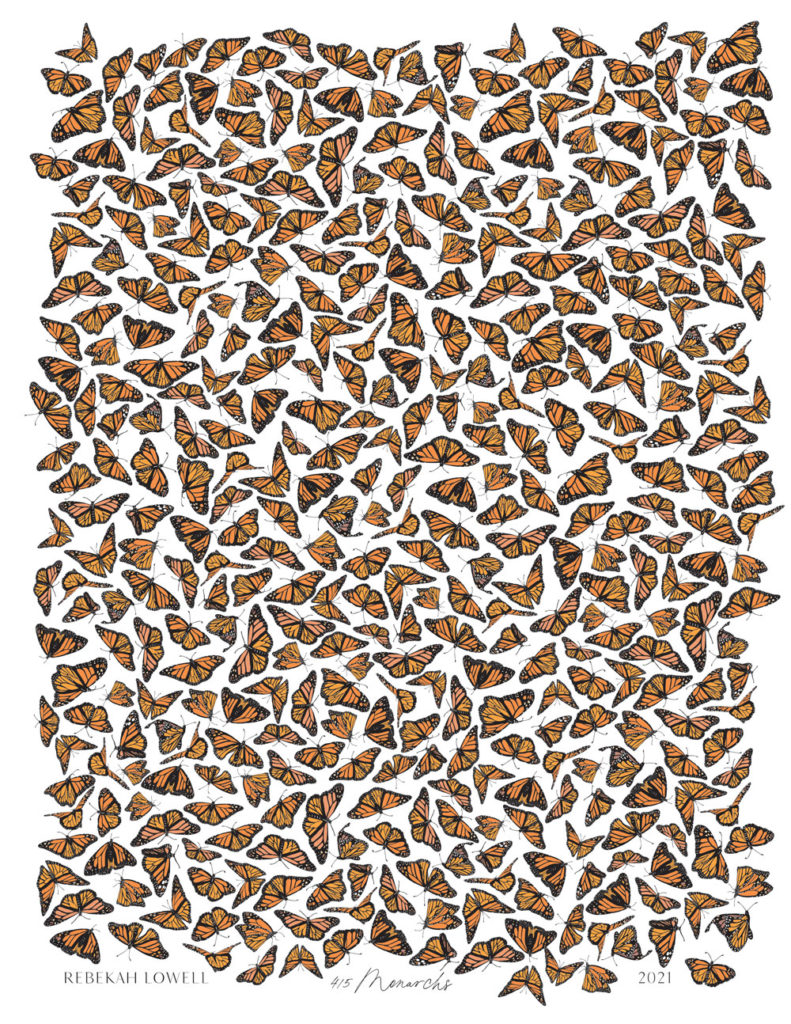

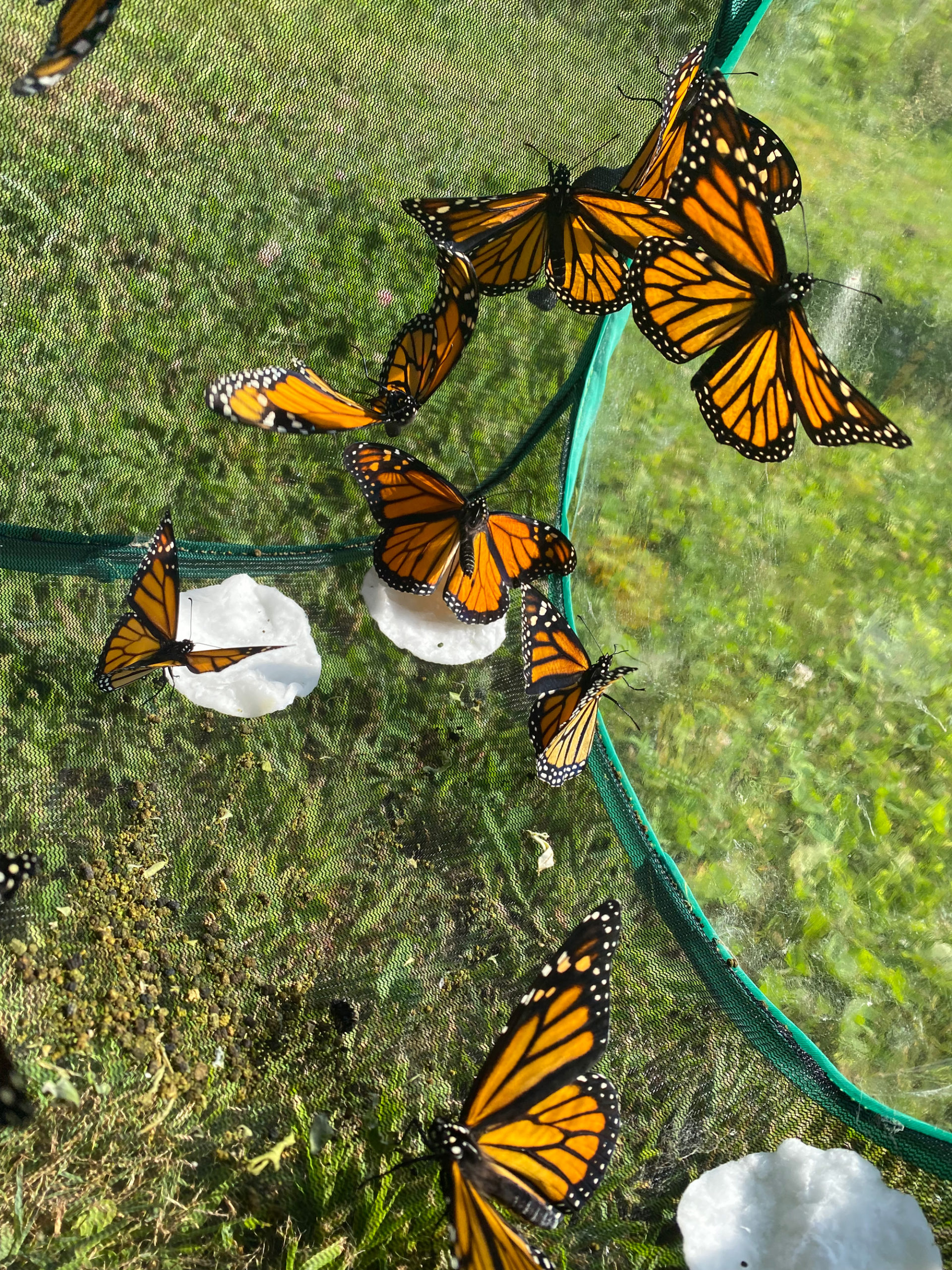

Observing the rhythms of the farmer haying the fields, I realized that I needed to search the field each daily because his arrival was based on conditions I didn’t know how to track— for example, the demands of his herd. So I ventured into the field more often, and with each summer, my numbers grew. During the season of 2021, I rescued and released 415 monarchs, most of them coming from that hayfield.

My Process

I clip stalks of milkweed with the eggs or caterpillars on them, and place them in mason jars that have holes poked in foil so the caterpillars don’t fall in. I place the jars carefully in mesh monarch habitats on folding tables. For eggs on single leaves, I lay the clipped leaf flat on a plate with damp paper towel at the clipped leaf stem. I have about 10 mesh habitats, but will probably use more in the future. The mesh keeps out predators such as beetles, spiders, and especially tachnid flies, which lay their eggs in caterpillars and parasitize them.

Following Nature

I have a small screen house that I place the mesh habitats in because being outdoors is best for the developing monarchs. Whenever there are storms or days with high wind gusts, I bring all the jars and plates with the eggs and cats inside, then return them outside when danger has passed. I know this is not ideal, but I would rather rescue the monarchs from the hay harvest than not at all.

In peak season, I spend about six hours per day tending the monarchs— searching for new milkweed, eggs, and caterpillars in the field, removing the old milkweed, inspecting each curled leaf on the old milkweed for any stray caterpillars who might be molting or hiding, and adding in the new milkweed to the habitats.

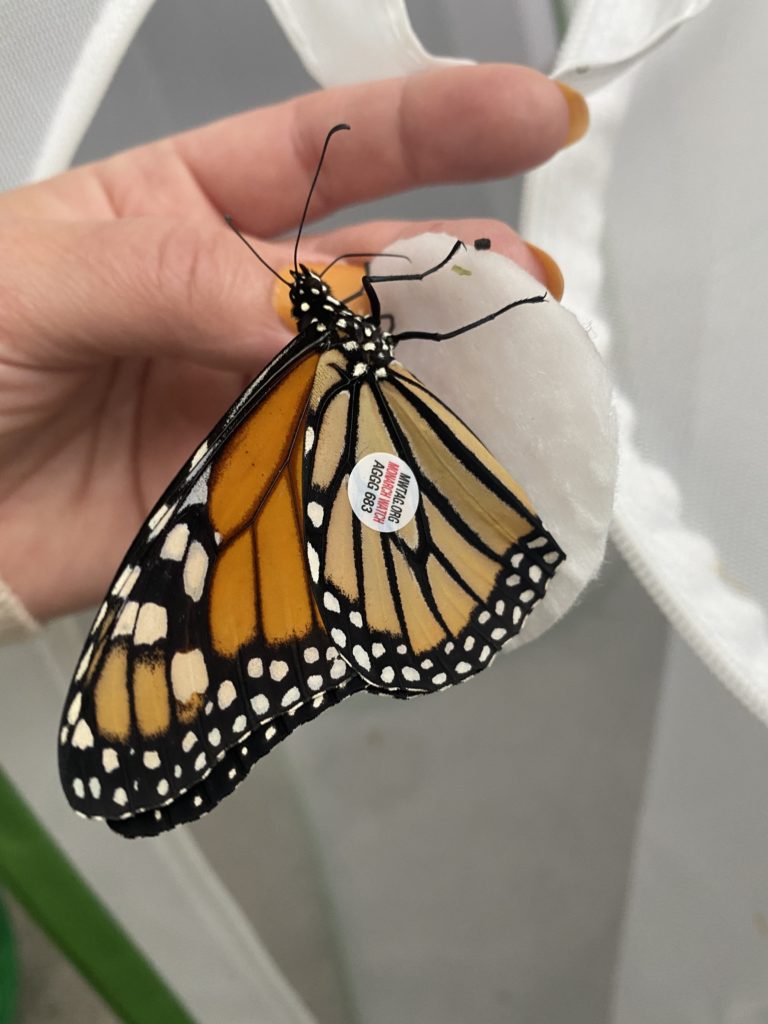

Tagging

After the monarchs eclose and their wings are dry enough (at least 5 hours) I tag one lower wing with a tiny sticker. I prefer to do this in the evening they are calm in dim light.

I learned of the tagging program with Monarch Watch only last year, and it was too late to tag for that season. Someone I met at the Coastal Maine Botanical Gardens said with my numbers I really should be tagging. I had already been considering it, but with their encouragement, I decided to try. Tagging the butterflies is a simple process, though it requires complete focus and attention so not to harm the butterfly.

Over the years I have released about 1,000 monarchs.

I began tagging in 2022, and will continue going forward.

One day, I hope to have a more stable structure to house the monarchs in, as eggs, cats, and chrysalides, so I can protect them from harsh weather while providing as much of the outdoor environment as possible giving them the best chance at life as I can.

Habitat Loss

Recently, only a mile from my house, there is a field near a home with about an acre of land that is abundant with milkweed. Each time I drive by it and admire the land, thinking of all the monarchs that are thriving in it. But, out of nowhere, during peak monarch season in August, it was mowed. I was devastated, gut punched. There must have been over 500 monarchs in various stages in that field, gone in one fell swoop.

I wondered if maybe they didn’t know. Milkweed that had been three and four feet tall, suddenly destroyed, along with its inhabitants.

I pulled into the yard, knocked on the door, but no one was home. I had planned to introduce myself and ask permission to search the field at the moment, but also in the future, to search the milkweed before they mow. Though I didn’t receive an answer at the door, I quickly searched the sliced milkweed anyway for any survivors and found two eggs. My youngest daughter was with me, and she searched too.

What if?

It was a hard scene to take in with so much milkweed fallen over, crushed, demolished, knowing what had been living in it. Had I had a larger enclosure, I could have introduced myself sooner to ask if I could collect their monarchs. I had considered that, but I didn’t have room in my habitats, and with no room to expand, I continued to drive by hoping they wouldn’t mow, hoping they would wait until October or November.

Hope alone didn’t save that field of hundreds of monarchs. I left feeling like I should have done something sooner.

This work is so important because the monarchs are on the endangered list. They need every chance they can get. Climate change, habitat loss, and predators all effect their rate of survival.

This year my numbers are only about half of last year. The drought caused the milkweed to turn yellow and shrink, and with less milkweed, there are less monarchs. Aside from being one of nature’s gifts to the sky for their joy, beauty, and symbolism, monarchs are key pollinators and are crucial to our ecosystem.

A Family Affair

My daughters are also involved in this work, helping me find milkweed, watching over the eclosing butterflies as they break free from the chrysalis in case they fall and have to be helped back up, and generally keeping an eye on them. This has been a key part to their homeschooling education.

I love teaching about the importance of monarchs and what we can do to help them survive such as planting milkweed, not pulling wild milkweed, growing pollinator gardens.

Raising awareness about monarchs through my art fills my heart with joy. It feels like my art has a greater purpose. It’s a perfect combination of two of my passions and heals my heart while healing our planet. What could be better?

Further Reading

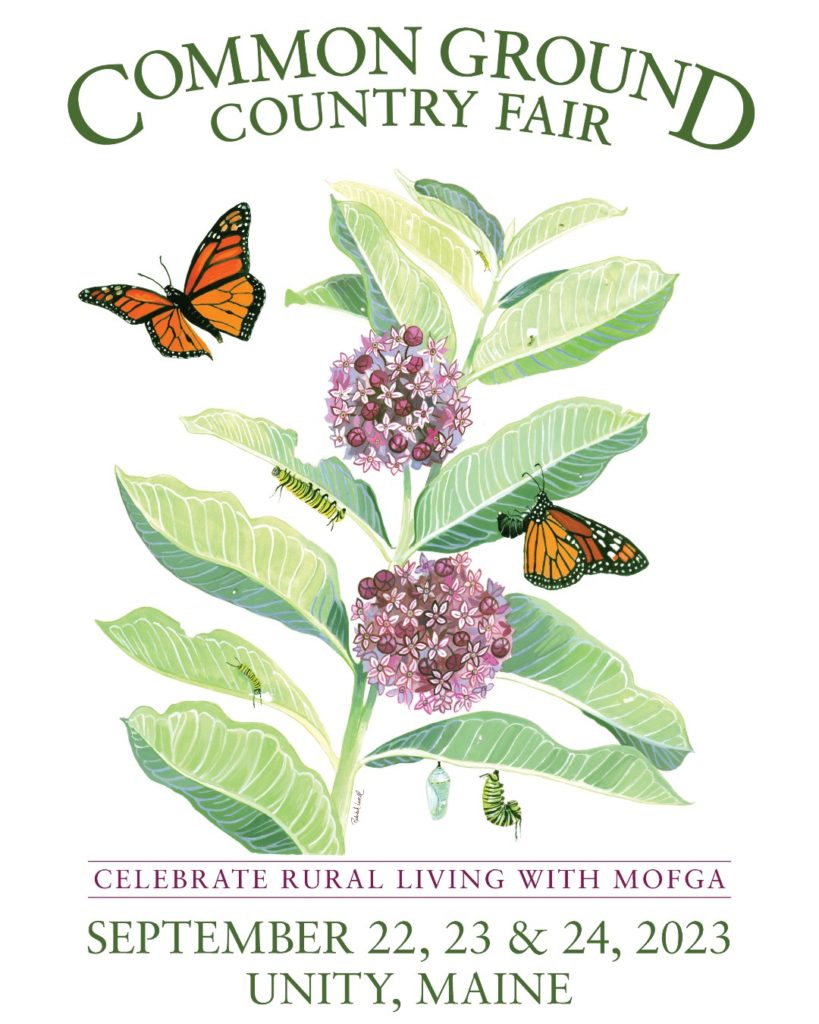

Read the news release from MOFGA here.

Here’s another article about the poster.

PSA

Plant milkweed!! (And don’t cut it down, please.) And plant native plants!

See you at the fair!

inspiration

Browse my favorite blog posts: inspiration, resources, and updates that I think you'll love.